Research

Genome evolution

My research examines the ways in which life history traits, and behavior in particular, can influence the way in which genomes evolve. During my PhD, I studied the genomics of plant-ant mutualism in ants and during my postdoc I have worked on the association between social evolution and genome evolution in bees.

Acacia-ant mutualism

Acacia-ants in the genus Pseudomyrmex are iconic examples of plant-ant mutualism. These ants obligately nest in the hollow thorns grown by acacias and feed exclusively on the extra-floral nectar and Beltian food bodies produced by their host plants. In exchange for this nesting space and food, the ants aggressively protect acacias against herbivores, pathogenic fungi, and encroaching plants. The ants are incredibly effective and plants without resident ants are quickly overrun by herbivory and disease.

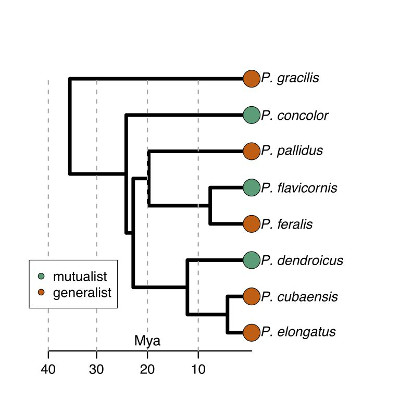

Plant-ant mutualism has evolved at least three times within Pseudomyrmex, making this an ideal group in which to study the evolution of this behavior. During my PhD, I compared the genomes of eight species within this genus, including three mutualistic species. Remarkably, these data show that mutualists all have higher rates of molecular evolution genome-wide. These results are now published here.

Further study and comparison with a clade of fungus-farming ants and bees have indicated that the likely mechanism underlying this shifting rate is likely due to the evolution of colony sizes. Taxa with larger colonies tend to have higher rates of molecular evolution as discussed here. Much of my research program is focussed on understanding the interaction of behavior and genome evolution.

Sociality in bees

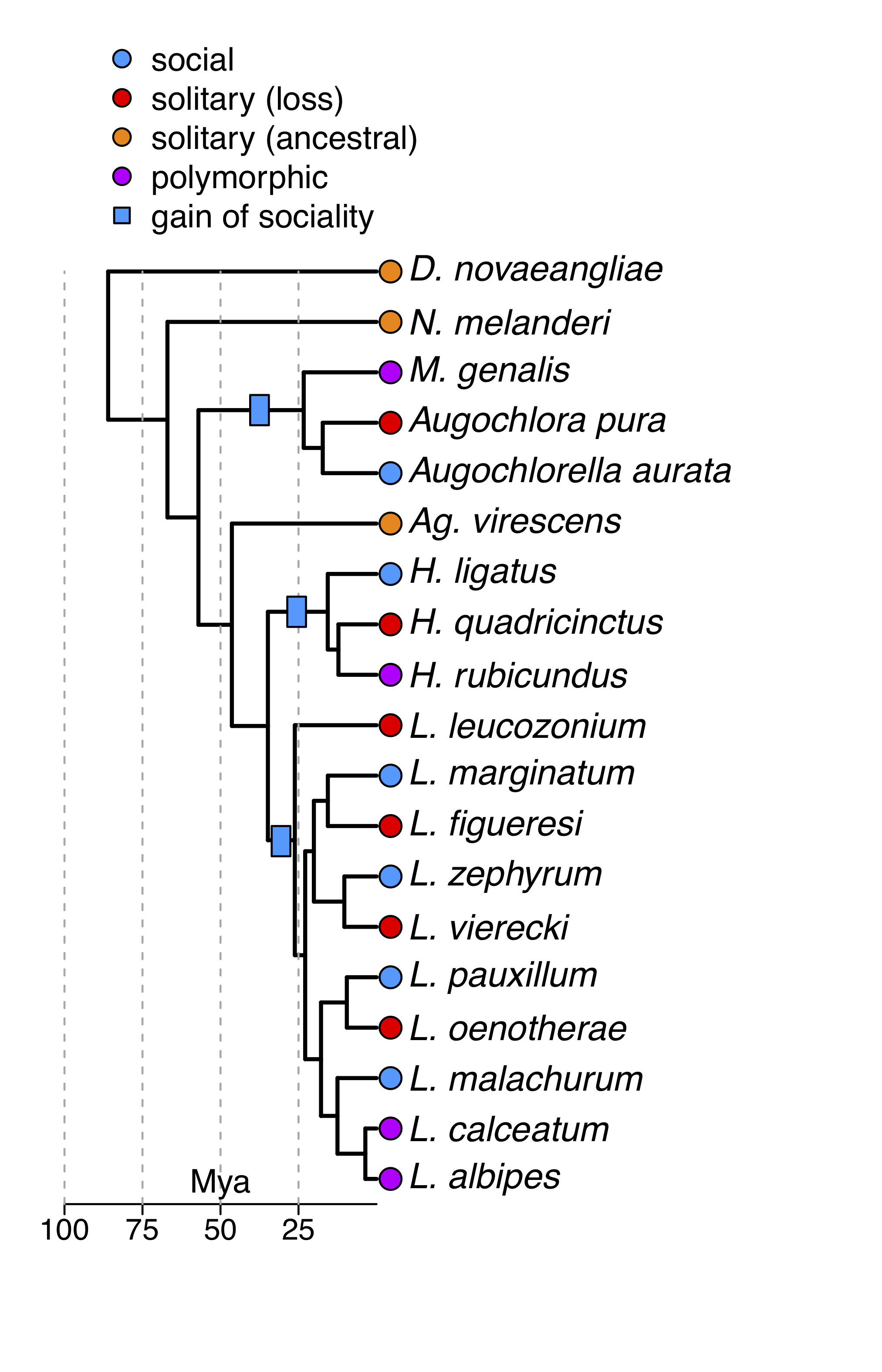

Bees in the family Halictidae, the sweat bees, are remarkably variable in sociality with even closely related species behaving very differently. I have sequenced the genomes of 16 species of these bees in order to identify the convergent genetic changes associated with social evolution.

While genome sequencing has become nearly routine during the past decade, many challenges remain for de novo assembly of non-model genomes. Through the use of linked-read libraries from 10x Genomics, Hi-C chromosome conformation capture data in order to place the resulting scaffolds onto chromosomes, increasing the power and quality of our analyses. I am now exploring the use of Oxford Nanopore sequencing for filling in the few remaining gaps in these assemblies. Using RNAseq data, ab initio prediction, and the integration of several gene-finding pipelines, I have also created high-quality gene annotations for these genomes.

By comparing the genomes of these 16 newly sequenced taxa and three previously sequenced genomes, I have found clear signatures of particular genomic features associated with social evolution. In addition, there are unexpected correlations between social behavior and rates of molecular evolution, suggesting that this shift in behavior may also have an influence on the genome as a whole. This pattern is highly representative of those on which I am most focussed.

Insect-associated microbes

Bacterial symbionts of insects are iconic examples of the interaction of life history evolution and genome evolution. When bacteria evolve obligate symbiosis with insects, their genomes degenerate, rapidly losing large numbers of genes. Therefore, I have also explored the microbial communities associated with both ants and bees.

Bacterial communities of acacia-ant mutualists

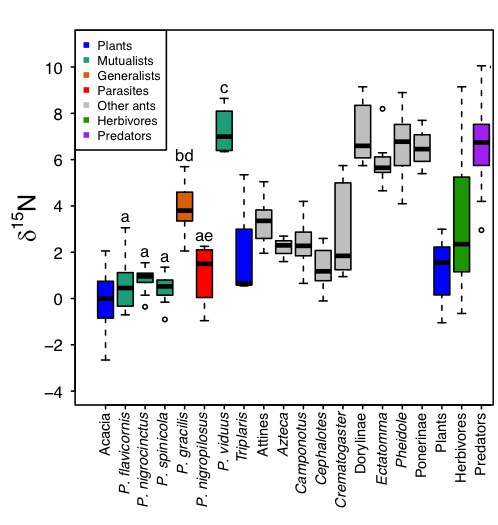

Ants are the most numerous animals in many terrestrial ecosystems, comprising over 90% of arthropods in the rainforest canopy. This numerical dominance means that ants cannot all be predatory, as was once thought, but must instead feed on more nutrient poor, plant-based resources. Acacia-ants are exemplars of strictly herbivorous ants, living in acacia trees and feeding exclusively on resources provided by these plants. However, the nutritional content of the nectar provided by acacias is insufficient for colony growth and reproduction, leaving open the question of how these ants obtain the necessary nourishment. Many other animals, including humans, are now known to depend on bacteria living in their guts to help them extract nutrients from their food. We, therefore, compared the bacterial communities associated with acacia-ants to related non-mutualists to determine if microbes may help to enrich their diets.

Instead of a particular bacterial community associated with acacia-ants, we found that community composition is correlated with trophic level, indicating that bacteria likely colonize ant guts based on diet, rather than acacia-ants depending on a specific lineage of coevolved bacteria for nutritional enrichment. Most excitingly, we found that a previously unknown bacterial lineage in the genus Tokpelaia, present in both mutualists and non-mutualists, possesses a complete nitrogen recycling pathway, and may contribute to the dietary enrichment of herbivorous ants in general. I am continuing to explore the function of these bacteria and their apparent evolution into obligate symbionts of ants. These findings have been published here.

Sociality and the evolution of symbionts

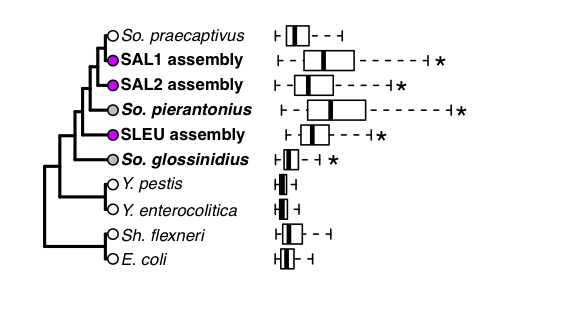

I recently found that several strains of bacteria in the genus Sodalis have independently colonized sweat bees (Halictidae). In every case, the genomes of these bacteria appear to be experiencing relaxed selection, suggesting a transition to obligate symbiosis. At least some of these strains are shared across bee species and geographic location but appear to compete with each other for territory when found together in the same individual bee. I plan to expand this line of research, what has predisposed Sodalis to repeatedly colonizing sweat bees. I will especially focus on the apparent competition between strains as these will likely be informative for understanding how insect-microbial symbioses stabilize over evolutionary time. Our first paper describing these findings is available here.

I have now received a postdoctoral fellowship from the USDA NIFA program to study the viruses associated with halictids as well. I am using molecular and bioinformatic techniques to characterize the viral communities in sweat bees and other non-model bees that provide important ecosystem services as pollinators.